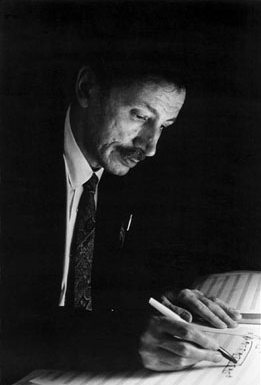

This is the fifth entry in the series of short log posts about pieces for solo woodwind instruments. The subject of this entry will be the Sonata for alto saxophone and piano composed by the Italian-American composer Paul Creston in 1939.

Born in New York to Italian parents, Paul Creston (1906-1985)1 was a self-taught composer, author, pianist and conductor whose vast output of over 150 works remain popular staples of large ensemble repertoire in the USA. This Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano is the first work that I have listened to which was composed exclusively for the saxophone. I am guilty of subconsciously slotting the saxophone everywhere and anywhere but the realm of what’s annoyingly called “classical” music, a stereotype for which I still have no explanation. I am aware of the expressive capabilities of the saxophone, in all of timbre, colour, phrasing, flexibility, tonality, etc., yet it is not an instrument that is often seen outside of popular styles like jazz, blues, and pop. I hope this piece inspires me to reach out to more music composed for this instrument and to promote it as it deserves.

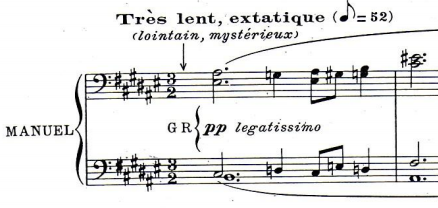

The Sonata follows a standard sonata first movement form and features both the piano and saxophone heavily. I was surprised that a piece with “accompaniment” was suggested as part of the list of compositions, however, this was very nice in hindsight. The full expressive potential of the saxophone is explored in this piece, particularly its ability to handle long flowing phrases with quick an subtle jumps in register. The full dynamic palette of the saxophone is also deployed with soft passages to aggressive fortissimo attacks.

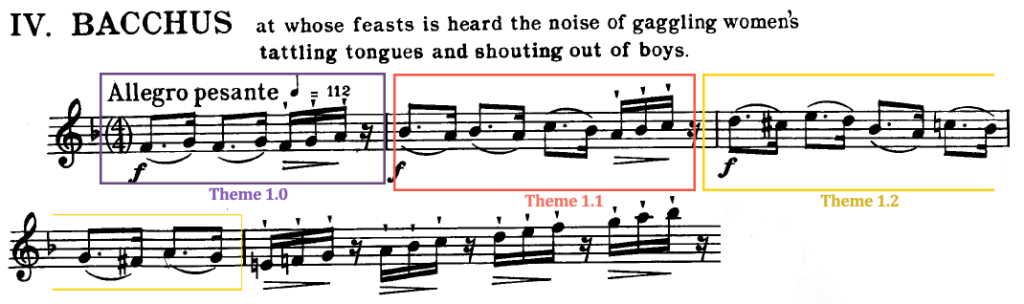

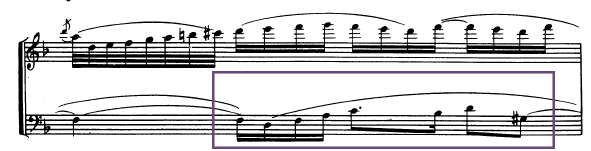

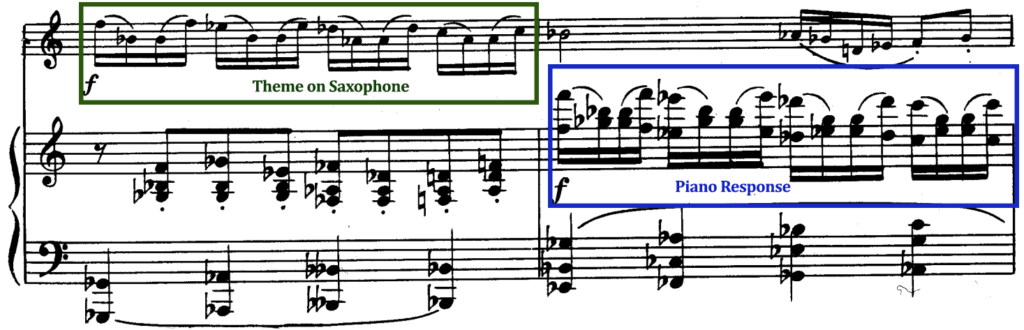

The tonality of the piece feels ambiguous at many points throughout, but the heavy emphasis on melodic lines (usually from the sax, but often carried in response by the piano, see image below) means that the ear is easily led in and out of any tonal centres with ease. There is also a heavy amount of chromaticism throughout, but this is never done without a sense of purpose and the piano is often there to guide the chromatic lines and to give them a wider harmonic context. Similarly, the meter of the piece can feel a bit ambiguous as both phrasing and accent are pushed and pulled beyond and before the natural strong beats.

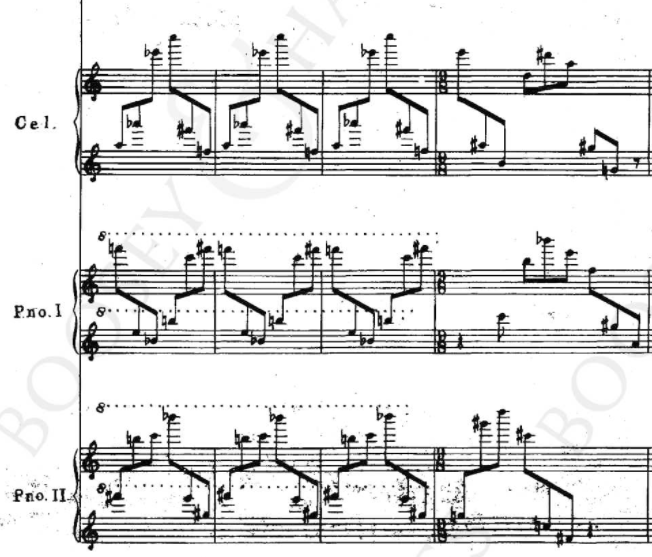

Although the focus of this entry is on the saxophone and woodwind instruments in general, an entire post could be done about the virtuosic piano parts. Although this work is regarded for its saxophone writing, the piano sections are very challenging and often feature on their own. The piano often provides really interesting counterpoint in the left hand to the saxophone’s lead, with the piano right hand doing most of the chordal work. Although the piano and saxophone operate in similar register in this piece, there’s never any ambiguity in who carries which section because of the difference in timbre and phrasing from each instrument as well as the contrasting features of the written parts.

This was a tremendously enjoyable piece to listen to, though not very challenging it has many elements which make it a really enjoyable listening experience. I would definitely recommend this as an introduction to compositions for the saxophone.

References: 1. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Paul-Creston Recording: Creston, P., Sinta, D., True, N. 2011. American Music. New York: Mark Records. [online] Sheet music: Creston, P. 1945. Sonata, Op. 19. Delaware: Shawnee Press. [online]