This blog entry will continue with the studies on polyphony, however tis will be the beginning of a short series on recommended pieces demonstrating contemporary takes on polyphony. For this first entry I listened to the first piece from the work Ten Pieces for Wind Quintet by Hungarian-Austrian composer György Ligeti (1923-2006).

Ligeti is a composer closely associated with avant-garde explorations in composition and form. His compositions often feature extensive use of electronics, closed tonal clusters, ambiguous sonority, and a concern for the interaction of sound in the environment.

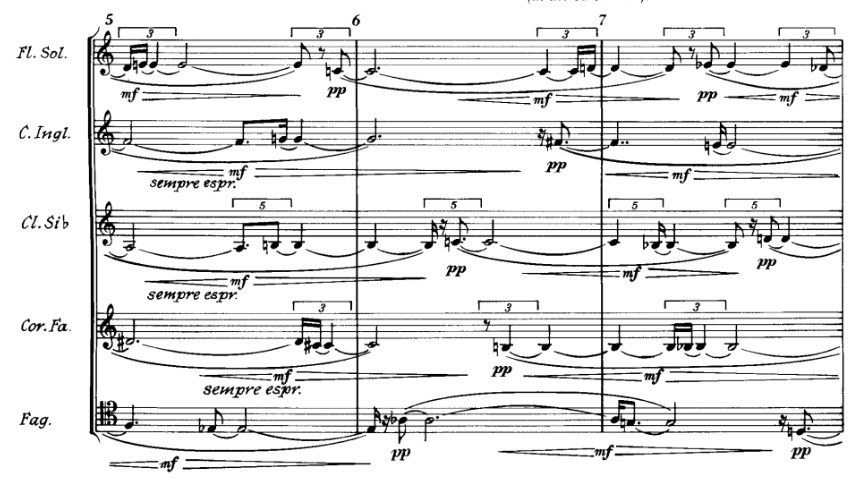

Ten Pieces for Wind Quintet is roughly organized into ensemble pieces (odd numbered) and solo pieces (even numbered). The main focus of this listening entry is on the first of these ten pieces (Molto Sostenuto e Calmo), which is an ensemble piece, where no discernible focus falls on any one voice within the quintet. The instrumentation is as follows:

Alto Flute in G English Horn Clarinet in Bb French Horn in F Bassoon

The piece has two distinct sections and these sections are not so much distinguishable due to a thematic change, but rather, there’s a distinct jump in register and a modulation in texture and dynamics. In the first section, the instruments move and change in ways that are not immediately apparent, there doesn’t seem to be any vertical coordination between the changes in notes from the instruments. The effect is that there seems to be a stumbling movement that is passed on horizontally from one instrument to the next. If this is combined with the staggered changes in dynamics, blunt crescendo/decrescendo pairs, then there is a feeling of constant falling experienced (I’m stretching it, but kind of like a Shepherd tone of sorts).

I’m very interested by this type of polyphonic writing now that I’ve had some more exposure to it. This particular piece subverts a lot of the traditions in polyphonic writing that I know of, yet it manages to allude to idea of staggered voice entries in traditional polyphony. I would imagine it would be interesting to analyze the intervalic movement of each voice and see if this is a patterned feature of the piece, but at first listen the implied movement of the piece, even if very slow and ambiguous, was a main focal point for my attention.