I couldn’t write a blog series on polyphony without dedicating at least one blog post to Thomas Tallis and his famous 40-part motet titled Spem in Alium (Hope in No Other), so this will cover some ground towards this giant of English renaissance music.

Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) was an English composer of the Renaissance period, and perhaps one of the greatest exponents of the English tradition of sacred choral music. Tallis composed Spem in Alium in or around 1570, likely inspired by a number of other equally ambitious works for multiple voices, or perhaps as a compositional challenge for himself. Spem in Alium owes part of its reputation to the monumental task of writing a piece that interweaves forty individual voices (eight five-part choirs, for a total of forty voices). Traditionally polyphonic vocal music would have been written for five voices, with further voices added to enrich the polyphonic texture of a composition, so it seems likely that Spem in Alium would have been composed to push the complexity of the style to new heights.

There is a lot that has been written about this piece already, and one of the most fascinating to me is the importance that the idea of space and cardinality play within the piece. It seems that the listener is not required to listen to individual voices and to try and make sense of a single moving line, it would be nearly impossible to do that even when only half of the choir is singing. Rather, the listener is invited to allow the ear to be guided by the movement of the sound itself, rather than by the movements of the voices up and down the register.

A performance of Spem in Alium might typically be performed “in the round” with the audience in the centre, which would create the spatial illusion of the music moving around the choir in different sections. Having even numbers (eight choirs, forty musicians) allows for a sense of cardinality to develop within the music where we can divide the choir into two halves, four quarters, and eight eights and to use this as a mechanism to preserve a balance in the music. This is obviously not a hard rule, as there are significant overlaps and transition moments between choirs, but it can be conceived in this way. I haven’t heard this piece performed live, but I find that listening to it with a score can be a close approximation if care is taken to visualize the layout of a performance and identify the position of each of the choirs within that layout. It can’t beat the real experience, but it does help.

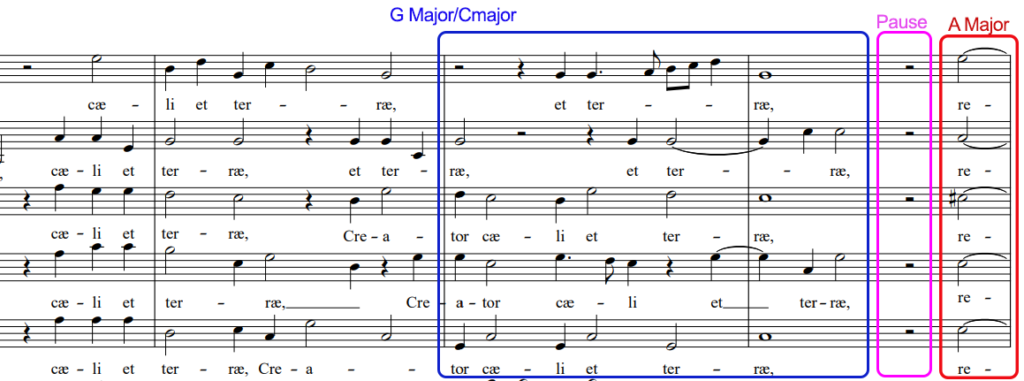

There are several striking sections in the piece that come as a shock every time I listen to this, as with every listen my ear goes somewhere else and loses track of where the choir is. There are least three distinct, jarring, and I would say violent stops where none of the choirs sing for a handful of pulses. These come at intervals of roughly every passing third of the piece. The resulting silence, after these continuous waves of sound, is very startling. In particular, after the last pause, there is a sudden and unexpected change in tonality from the preceding C Major to A major, in a weak beat of the bar. Though I struggle to anticipate it with every listen, and I know it’s coming, it’s always such a pleasant and eye opening change.

I can’t imagine what performing or conducting this piece must be like. I would imagine sectionals are being arranged so that each choir can function individually before being brought together. Furthermore, since the audience has trouble discerning the different voices, I would imagine performers might be taking their cues from singers around them, which can be tricky if the choirs are trading sections in the music but are not adjacent to each other physically in the performance space.

References: 1. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Tallis Recording: Tallis, T., Choir of the King's College, Cambridge. (1992) "Spem in Alium" Tallis: Spem in Alium. London: Decca.